by Anna Katharina Seitzer (University of Regensburg)

The armistice of Compiègne, signed by France and the German Empire on June 22, 1940, ended the military offensive of the German Wehrmacht in Western Europe. Although the German Empire was still at war with Great Britain, the leading National Socialists decided – against former calculations – to turn their attention to the war against the Soviet Union.1 The lack of cover in the West was meant to be compensated by the cover of the northern and southern flank of the Reich. In relation to the Southeast European war theatre, this meant the consolidation of the pre-existing economic connections between the Reich and the Balkan States.2 Hitler tried to stabilize Germany’s powerful position in the Balkans before anything else; the Balkans was supposed to act as a transit area and deployment zone of German troops and their allies against the Soviet Union. With the accession of Hungary, Romania, Slovakia and Bulgaria to the Tripartite Pact on the September 27, 1940, the political connection between the Balkan States and the Reich became official.3

Berlin’s attempt to prevent any military or political conflict in the Balkans in order make use of the state’s pre-existing economic connections for the future warfare, ended with the Italian attack on Greece via Albania on October 28, 1940.4 This attack led to an immediate military reaction from Great Britain, which had given a guarantee to Greece on April 13, 1940. Yet, as the Italian offensive against Greece failed and the defeat of the Italian Army became obvious, Italy asked its German partner for military support.

Hitler was afraid both of losing the hegemony of the Axis forces in the South-East and of the British locking in the Balkans, which could disturb his war against the Soviet Union.5 For this reason he issued his instruction No 20, the so-called “Operation Marita”, on December 13, 1940.6

The German troops began their attack on April 6, 19417, with the bombing of the “Metaxas-Line”8 along the Greco-Bulgarian border. The Twelfth Army invaded Greece via Bulgaria. After the capture of the two Thracian cities Komotini and Xanthi, the troops seized the Macedonian seaport of Thessaloniki on April 9. From there, they pushed forward towards the west, took over Florina and occupied the Thessalian towns of Neapolis and Grebena after crossing the Aliakmon River. Following this, the Wehrmacht moved towards Central Greece. With the German capture of Kalambaka and Lamia, the Greek Army surrendered unconditionally on April 23, 1941. Still, the clashes were still not over: the German Army encountered resistance from the last British troops stationed in Greece. It was only after the capture of Thebes that the last British troops were evacuated. Early in May 1941, Athens, the Peloponnese and all of the important isles except Crete were occupied by the Axis forces. The German attack on Crete, “Operation Merkur”9, ended on June 1, 1941 and marked the complete annexation of Greece.10

After the occupation of the Greek state’s territory, the land was divided among the Axis forces who participated in the attack on Greece: Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. In this sense, three occupied areas were formed. The area Germany occupied was – at that time – the smallest.11

The acting government, Emmanouel Tsouderos and King Georg II escaped to Crete on April 23, 1941, from where they continued on to Cairo and then partially to London. A parallel collaborationist government was set up by the Germans in occupied Greece. This government absolutely depended on the occupying forces. The Axis dictated both the composition of personnel and the political orientation of the cabinets. The first “puppet regime”12 under Georgios Tsolakoglou13 was appointed on May 1, 1941. Georgios Tsolakoglou was followed by two further prime ministers: Konstantinos Logothetopoulos, who was appointed in November 1942, and Ioannis Rhallis, who was appointed in April 1943.14

In parallel to the establishment of a puppet regime, a military regime was built up in the German occupation area which lasted until the autumn of 1944. In addition to military authorities, a German police force, a defense economy department, a war department belonging to the OKW (Supreme High Command of the German Armed Forces) and civil departments of the German administration of occupied territory were established.

The regime ran a radical economic policy and it had to finance the occupation costs. This led to the devaluation of the Greek currency and as a consequence, to a period of economic recession in Greece between 1941 and 1944. The systematic exploitation of the Greek population through the diversion of essentials goods which were needed to sustain the German war effort, led to a constant food shortage during the whole period of occupation. Between September 1941 and August 1942, 50,000 people died of hunger in Athens alone.15

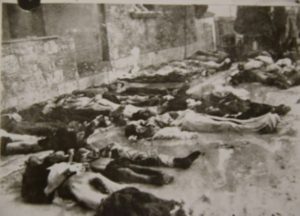

Athens, winter 1941/42 (Source: State Archives Athens)

People starved to death, 1941/42 (Source: State Archives Athens)

From the very beginning of the occupation, the occupation forces tried to bring Greece under control and to “pacify” the country.16 This meant – as a first step – to fight against the Greek partisan movements, which had quickly emerged. These movements committed acts of sabotage and encroachment against German troops and establishments. The successive increase of the activities of the resistance, combined with the fear of an invasion of the Allied troops beginning in the summer of 1943, led to the decreeing of countless cruel reprisal actions.17 Theses initial measures against the partisans were of little avail, the German actions soon focused on non-participant civilians, who were only suspected of dealing with partisans or of supporting them.

The brutality of the German army increased. This is evidenced by the destruction of whole villages and the killing of all inhabitants, the taking of hostages, in public executions or in the removal of suspects to concentration camps. The brutal behavior of the soldiers in Greece was in accordance with German military guidelines. This military agenda regulated the authority of the occupying forces declaring that control should be enforced through the “strongest means”18 and stated that German military personnel’s “actions must not be persecuted.”19 Apart from the massacre committed by the Wehrmacht in Komeno in August 1943, or in Kalavryta in December of the same year, the massacre of Distomo by SS-troops on June 10, 1944, is one of the most notorious examples of German war crimes in Greece. The attack on Distomo was officially justified as a so-called “measure of reprisal” because of a partisan attack. In reality, it was an arbitrary “act of revenge” by the Second Company of the Fourth SS-Polizei-Panzergrenadierdivison commanded by SS-Commander Fritz Lauterbach. In the course of this act of revenge against the peaceful village Distomo, 218 civilians were brutally slayed and in the end the village was burned. The victims were mostly women, elderly people and children, of whom 38 were between ten years and two month. The prefect of Boeotia, Ioannis Georgopoulos, filed a report about what happened in Distomo for the Greek Ministry of the Interior based on testimonials by witnesses. An English translation of this document reached the State Department via the American honorary consul in Istanbul, Burton Y. Berry. This source stressed the “sadistic excesses” committed by the SS soldiers:20

“Girls, wives of officials and villagers, were raped and their breasts were cut off. […] Groups of soldiers went to the houses and executed all the inhabitants without pity, unmoved by their pleas. They spared no one. The head of the family first, the wife next, and then the children. Infants had their throats cut. A child was found with the cut-off breast of its mother in its mouth, wounded in the middle of the forehead and in the neck. The child of the Justice of Peace, Grotzopis, who was killed, and his wife, who was raped and killed, was found, beaten, on the next day beside the body of his father, which he did not want to leave. Another wounded child was found wailing on the bodies of its mother and father, the forester Kouroumpalis. The entrails of four other villagers were found wound around his neck. The priest of the village was found headless. His head, which was found a short distance away, had the eyes gouged out.”21

Germany also applied the Nazi ideology with regard to the Jewish population in the occupied territories. According to this ideology, the Greek Jews should be extinguished with the aim of establishing a racially homogenous population. The persecution of the Jews in Greece followed the patterns of action established in other occupied countries, beginning with the registration of the Jews which was followed by their successive exclusion. Their dispossession22 was followed by deportation and murder.23 The territory occupied by the Germans was the smallest in size, but included the majority of the Jewish population. The German measures of ethnic cleansing started in Thessaloniki, which hosted the largest Jewish community in the country. The so-called “Final Solution of the Jewish Question”24 was set into action on February 6, 1943, with the decree “MV 1237”, which fixed the identification and resettlement of the Jews of Thessaloniki.25 It was followed by numerous orders to exclude Jews from public life, for example through the implementation of regulations ordering the labelling of Jewish businesses or a trade ban. In March 1943, the demarcation of ghetto areas in Thessaloniki and the resettlement of all Jews from Thessaloniki into these areas, which were completely sealed off, began.26 The deportations from the Baron-Hirsch-Ghetto began on March 15, 1943. On August 11, 1943, the last train from Thessaloniki to Auschwitz departed; 46,000 Jews had been deported.27 After the capitulation of by Italy on September 8, 1943, German troops started to persecute Jews in territories formerly occupied by Italy. This included communities in and around Athens and Ioannina as well as the communities on the Islands of Kreta, Korfu, Rhodos and Kos. Altogether, 21 deportation trains with 53,789 people left Greece for Auschwitz.28 In Auschwitz these people found their death in the gas chambers, through “extermination through labor”, or died as a result of the inhumane conditions of their detention.29

Statistics of the eighteen deportation trains from Thessaloniki to Auschwitz in 1943

| Departure from Thessaloniki | Arrival in Auschwitz | Number of

deportees |

Committed to the camp as prisoners | Instantly murdered in the gas chambers |

| 15 March 1943 | 20 March 1943 | 2,400 | 609 | 1,791 |

| 17 March 1943 | 24 March 1943 | 2,500 | 814 | 1,686 |

| 19 March 1943 | 25 March 1943 | 2,500 | 695 | 1,805 |

| 23 March 1943 | 30 March 1943 | 2,501 | 453 | 2,048 |

| 27 March 1943 | 3 April 1943 | 3,500 | 592 | 2,908 |

| 3 April 1943 | 9 April 1943 | 2,251 | 479 | 1,772 |

| 5 April 1943 | 10 April 1943 | 2,750 | 783 | 1,967 |

| 7 April 1943 | 13 April 1943 | 2,800 | 864 | 1,936 |

| 10 April 1943 | 17 April 1943 | 3,000 | 729 | 2,271 |

| 13 April 1943 | 18 April 1943 | 2,501 | 605 | 1,896 |

| 16 April 1943 | 22 April 1943 | 2,800 | 668 | 2,132 |

| 20 April 1943 | 26 April 1943 | 2,700 | 638 | 2,062 |

| 22 April 1943 | 28 April 1943 | 3,070 | 541 | 2,529 |

| 28 April 1943 | 4 May 1943 | 2,930 | 538 | 2,392 |

| 3 May 1943 | 7/8 May 1943 | 2,600 | 883 | 1,717 |

| 9 May 1943 | 16 May 1943 | 1,700 | 677 | 4,023 |

| 1 June 1943 | 8 June 1943 | 820 | 308 | 512 |

| 11 August 1943 | 18 August 1943 | 1,800 | 271 | 1,529 |

| Total | 45,123 | 11,147 | 33,976 |

Source: Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 296-7.

As in other countries occupied by the Germans, the Greek Jews received help and support from certain groups within the population. The Orthodox Church, for example, baptized Jews to get them, “out of the firing line.”30 But the “most significant successes in terms of help and support” was achieved by the resistance movement against the occupation.31 They called on the population to show solidarity, helped Jews to go underground or smuggled them into the Middle East.32 However, like in all other occupied countries, there were also many non-Jewish Greeks in Thessaloniki which turned a blind eye on the round-up of the Jews or even felt comfortable with the deportations.

The misery of the population caused by the permanent food shortage, the economic exploitation of the country and the situation of occupation in general enforced by the Axis forces bolstered the emergence of the Greek Resistance. The most powerful organization, the left-wing National Liberation Front (EAM), was formed on September 27, 1941. This group was mainly influenced by the Greek Communist Party. The military arm of the EAM, which was first mentioned in April 1942, was called the Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS).33 The EAM focused on the “absolute fight against the occupiers and the collaborationists” with the aim of holding free elections following the successful struggle for liberation against the occupiers.34 The EAM/ELAS never gave up this aim until the end of the occupation. Besides the EAM, the National Republican Greek League (EDES) was formed on September 9, 1941. Its initially “anti-monarchist and socialist” statute was remarkable because it “failed to mention the occupiers.”35 As the EDES was successively subject to infiltration by the right, their initial aims shifted towards pursuing a pro-British course. This meant the re-establishment of the monarchy in Greece after the conclusion of the occupation and towards negotiations with the German occupation force. The increasing tension between the groups of the resistance was supported by British and German propaganda in favour of segregation, which led to the first open conflict on October 10, 1941.

As the war situation for Germany worsened in all of its European positions, the Wehrmacht started to leave Greece on August 26, 1944.36 On September 21, the withdrawal from the Peloponnese was completed. On September 27, the withdrawal of troops from the west of Greece all the way to the Pindus followed. On October 7 the withdrawal of Attica was initiated and on October 13, 1944 the last German soldiers left Athens. There, the troops laid a wreath at the tomb of the Unknown Soldier to demonstrate that “the Germans didn’t come to Greece as enemies.”37

This assertion is contradicted by the record of the occupation regime: tens of thousands of civilians died during the terror, approximately 50,000 Jews were killed, and hundreds of thousands of people starved to death. In certain regions, 60-70% of the population suffered from epidemic diseases. In addition to the horrible decimation of the Greek population, the material loss of the state was also dramatic. The economic exploitation of the country during the time of occupation was strengthened by, “large scale of actions of destruction during the withdrawal from the German troops in October 1944.”38 In this context, 75% of the Greek railway system and the majority of the main stations and harbors, as well as close to 200,000 houses were totally or partly destroyed.39

- Andreas, Wirsching, „Man kann nur den Boden Germanisieren“. Eine neue Quelle zu Hitlers Reden vor den Spitzen der Reichswehr am 3. Februar 1933, Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 49, No.3 (2011). This article works with an interesting source which focuses on one of Hitler’s early speeches. In it, Hitler discusses his plans concerning the living space for Germans in the East. Here it becomes evident that Hitler wanted the war with the Soviet Union already in 1933. ↩

- As an example of the pre-existing connections there is the so-called “Oil-Arms-Pact” between the Reich and Romania made in May 1940. The primary goal of the pact was to secure the oilfields of Ploiesti against destruction or seizure. ↩

- Hungary joined the Tripartite Pact on the 20th of November, 1940, Romania on the 23rd of November, 1940, Slovakia on the 24th of November, 1940, and Bulgaria on the 1st of March, 1942. ↩

- Hagen, Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte. Griechenland 1941-1944, Frankfurt ( Main) 1986, 52. ↩

- Weisung Nr. 21. Fall Barbarossa, in: Walther, Hubatsch, Hitlers Weisungen für die Kriegsführung. 1939-1945. Dokumente des Oberkommandos der Wehrmacht, München 1965, 96-107. ↩

- Weisung Nr. 20. Unternehmen Marita, in: Hubatsch, Hitlers Weisungen für die Kriegsführung.1939-1945, 94-96. ↩

- Telegramm des Reichsaußenministers an die Gesandtschaft in Athen vom 5. April 1941, in: Anestis, Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944. Deutsche Besatzungspolitik und Verbrechen gegen die Zivilbevölkerung – eine Beurteilung nach dem Völkerrecht, Göttingen 2009. (=Osnabrücker Schriften zur Rechtsgeschichte 15), 45. ↩

- Karte der Operationen in Südjugoslawien und Griechenland vom 6 – 30 April 1941, in: Gerhard, Schreiber u.a., Der Mittelmeerraum und Südosteuropa. Von der „non belligeranza“ Italiens bis zum Kriegseintritt der Vereinigten Staaten, in, Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt (Hg.), Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, Bd. 3, Stuttgart 1984, 461. ↩

- Weisung Nr. 28. Unternehmen Merkur, in: Hubatsch, Hitlers Weisungen für die Kriegsführung, S. 134-135. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 45- 47. ↩

- Mark, Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece. The Experience of Occupation, 1941-1944. New Haven and London 1993, 21. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 70-77. ↩

- Documents on German Foreign Policy, Series D, 1941, 722. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1918-1945, 71. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 387-390. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 187. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 192f. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 188. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 189. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 228. ↩

- Report of the prefect of Boeotia to the Greek Ministry of the Interior dated 13 June 1944, cited by Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 229. ↩

- Arne Strohmeyer, „In Polen wartet eine neue Heimat auf euch!“ Wie die NS-Stellen, die Wehrmacht und die SS in Griechenland den Holocaust durchführten.“, in: Blume, H.-D. / Lienau, C., eds., Choregia, Münsterische Griechenland-Studien 10. Münster 2012, 85-6. Here, the dispossession of the Jews is explained as a way in which to ensure the Wehrmacht’s supplies and to achieve the goal of fighting inflation in Greece. ↩

- Strohmeyer, „In Polen wartet eine neue Heimat auf euch!“, 67f. ↩

- Strohmeyer, „In Polen wartet eine neue Heimat auf euch!“, 72. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 292. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 295. Three ghettos existed in Thessaloniki: the Baron-Hirsch Ghetto, and the city areas Ajia Paraskevi and Regia Vardar. ↩

- Strohmeyer, „In Polen wartet eine neue Heimat auf euch!“, 76. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 307. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 307. ↩

- Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte. Griechenland 1941-1944, 367. ↩

- Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte. Griechenland 1941-1944, 367. ↩

- cf. Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte. Griechenland 1941-1944, 367. ↩

- Mazower, Inside Hitler’s Greece, 106. ↩

- Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte. Griechenland 1941-1944, 94. ↩

- Fleischer, Im Kreuzschatten der Mächte. Griechenland 1941-1944, 96. ↩

- Heinz, Richter, Griechenland zwischen Revolution und Konterrevolution (1936-1946). Frankfurt (Main) 1973, 484. ↩

- Fleischer, Die deutsche Besatzung(spolitik) in Griechenland und ihre „Bewältigung“, 8. ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 39 ↩

- Nessou, Griechenland 1941-1944, 397; Fleischer, Die deutsche Besatzung(spolitik) in Griechenland und ihre „Bewältigung“, 8. ↩