by Valentin Kordas (University of Regensburg)

Introduction

The reasons why so many Greek people came to Germany after the signing of the recruitment treaty between the two countries in 1960 are so diverse that a universal assessment of these individual motivations seems impossible. Each migrant worker had his or her own ideas, expectations, dreams and personal history.

What was going on in the minds of those, who decided to leave the place of their childhood, of their memories, and of their former life in order to start once again in a new country? In this essay, I will reflect on this question by examining the concrete experiences of a Greek migrant worker. My approach can be called a collaborative one, engaging one individual and his memory. We spent time together talking about his life, the life of his family, his opinions and experiences; we drove around to places important to him and his family. We entered into constant communication and once the text of my essay was ready, I had the interviewee review it. It was important for me not to impose my own interpretation on his, and the other migrant workers’, experiences. I wanted to achieve a dialogue which confronted my own ideas about the topic with the interviewee’s representations and evocations of memory. In line with the concept of “collaborative ethnography” I do not consider the interviewee an “informant”.1 He should rather be seen as a colleague and partner who helped to make his individual experience comprehensible in the context of the larger topic of Greek labour migration to Germany. This essay, therefore, is not concerned with any kind of statistically measurable history, political events, or legal texts. These conditional factors are largely known, or can easily be investigated: but what were the small experiences lying behind such generic terms as “migrant workers”? These do not appear in aggregate statistics, train timetables or Social Security numbers.

Getting ready

The headwind blows, distributing the smell of nicotine inside the blue BMW. The imperceptible scent of thyme from outside, mixed with the taste of old cigarettes in the car.

„That [thyme] grows everywhere ‚round the roadside. 50 years ago, my sister and I walked over these hills for days to get from one village to the other. At ALDI you have to pay 1€ at least.“

It is April 14, 2015. Efthimios or how his friends call him, Themi, drives through the countryside between Trikala and some mountain villages, heading to Mavreli, the place where he left his childhood. Passing by the rusty village sign we bump into a quiet scene. An old women dressed in all-black is on the street, while two old men sit in their courtyard, following with their eyes the slow moving blue Bavarian car. Visitors are usually not looking for places like this. Walking through his mother’s house, old pictures on the stone wall remind Efthimios of a nearly forgotten life. We walk around a cold and dusty fireplace.

„I do not exactly remember, but I think it was at the beginnings of the 1960s. I must have been seven or eight years old. My auntie took care of my sister and myself when my mother, Evangelia, departed to Germany.“

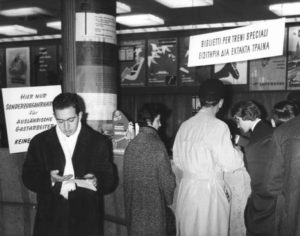

Evangelia was not the only person from the village who left for Germany. In 1961, one year after the conclusion of the recruitment agreement between the West German and the Greek governments, cousins, friends and other relatives of hers were among the first Greek migrant workers, who started their journey northwards to Germany. Before the train doors would close behind them, they had to undergo a rigorous selection process. Efthimios relates how his mother waited with other people in a row to get into the doctor’s room. The doctor examined her very carefully and afterwards certified with a stamp that she was healthy and able to work in Germany.

She, her nephew Lambro and his wife Dorothea took the Hellas-Express to Nuremberg. They possessed employment contracts with HERCULES, a bike manufacturing company named after the hero from Greek mythology. Other friends and cousins from Mavreli proceeded to Bremen. Most of them still live and work there in Greek taverns that bear names like “Restaurant Dionysos”.

It was not unusual for whole villages to migrate to the same place in Germany.

One leaves, others follow.

Most of them were young people who were in good physical constitution to face the long journey and the new environment. But their links to Greece were not cut off at all. During holidays, such as at Christmas or during the summer, almost everybody returned to Greece. In their luggage, they also brought savings from their earnings. Thus, the relatives who were not able to leave Greece benefitted from their sons‘ and daughters‘ work, as they received a part of their paychecks.

Long lasting arrival

When Efthimios‘ mother arrived in Munich she was led to a room near the train station. She and the other migrants received a number – each number stood for the eventual destination in the new country. A company representative waited in the entrance hall to meet her. She and many other passengers were put on a bus that brought them to the city where they would start their work. In this case, it was Nuremberg.

„I remember when she called me. The first thing she asked was if it was so cold in Trikala too. That was a problem for her. […] I don’t remember very much the details of her journey. I think it was nothing special. Neither especially joyful nor particularly tragic. It was work.“

Many former migrant workers commented on their plans for their stay in Germany in similar ways. There was no idea of a future life in Germany. The whole country was a synonym for hard work and the chance to earn money, but not for taking part in any social life. Only a very small number of the migrants wanted to stay in Germany forever. The idea, rather, was to work a job for a limited time in order to earn enough money for a worriless life in Greece.

The German government also did not create conditions for continuous residence. Migrant workers were allowed to stay only as long as their employment contracts lasted. This also had an impact on the political participation of the migrant workers; they did not enjoy voting rights and there were hardly any other means of public participation for them. The German government also did not support their inclusion in the representative bodies of workers in order to separate the migrant workers from the domestic proletarians. The new proletariat from southern Europe was marginalized, so that the domestic workers had someone to look down upon.2 The exclusion of the migrant workers from political participation created a vicious cycle. Human beings who have no chance to make their voices heard from the outset will not waste time on efforts to integrate themselves into society.

Efthimios sits in front of the old house, the sun lightens up the rocks on the hilly countryside.

„I think it was hard for my mother. My father died, when I was three, and she had two kids to feed. Difficult without a job, without an apprenticeship and without any money. But also difficult in a foreign country without anything. What would you do? Leave.“

So she left like many other women whose husbands, friends, brothers, fathers or cousins took the trip to Germany.

After fifty hours on the train and another three hours on the bus, while many unfamiliar impressions rolled past the window, she stood in a room of a dormitory near her new workplace. The only advantage she saw was that she shared a room with other Greek people. About thirty square metres of Greece in a bare room framed by heating pipes in pale-yellow colours.

A few times a week she took the phone and called home, asking how the kids were doing and giving them orders like cutting wood, collecting tobacco or checking the water in the well.

After the first two weeks in the bike factory she reported home, against all stereotypes, that she and the other workers were well treated by the Germans. Every day she received a nice “good morning” by her boss. He often asked whether she felt well or if she needed something. The problem was rather the time after work. She said on the phone that she felt lonely. The men went to cafés, playing cards and backgammon, and to have drinks. But in those times, such kind of after-work entertainment was unusual for a woman from a Greek village. So she stayed at home and spent her time watching TV or listening to Greek radio shows in order to keep herself up-to-date.

Politics killed the radio star

In March 1960, German radio introduced radio broadcasts for migrant workers in their own languages. The Greek programmes produced by Bavarian Radio-Television were often the only source of information for the Greeks while they sat in their dormitories or flats. A central figure in this was Pavlos Bakogiannis, who headed the Greek radio program Bayerischer Rundfunk for ten years, beginning in the mid-1960s. His programme informed listeners about the political events in Greece, as well as about topics of concern for Greek citizens in Germany. It focused on information about socio-political issues relevant to migrant workers, such as labour law and economic problems. The journalists on the program also took on the role of life coaches, sharing information about insurance, unemployment benefits, new regulations or what kind of vaccination was advisable.

Before the military coup d’état in Greece in 1967, the editors of the programme could produce the content without any external intervention. However, once the military dictatorship was established, it increasingly began to criticize the “Gastarbeitersendungen” (broadcasts for migrant workers). Representatives of the Greek junta argued that foreign media would intervene in internal Greek affairs and stimulate political radicalization. This went so far as the Greek Consul-General in Munich, Mr. Economou, who even lodged a complaint with the Bavarian State Chancellery. The then head of the Bavarian government, Alfons Goppel, passed on the complaint to Christian Wallenreiter, the director-general of Bavarian Radio-Television. Wallenreiter was then summoned by the Federal Foreign Office. He was reprimanded, as the Greek broadcasts could endanger the economic and international relations between Greece and Germany.

Such interventions, of course, were an infringement on the constitutionally guaranteed freedom of the press. In contrast to the right to vote, freedom of the press was valid for all people within the borders of West Germany. Nevertheless, the former broadcast director Walter von Cube put the political comments of the Gastarbeitersendungen on hold in order to remove tensions with Athens.

The food dilemma

Ten years and 250,000 migrant workers later, Efthimios packed his bags and left too. However, not as an ordinary migrant worker. Due to the imposition of the military dictatorship, he could not imagine a future for himself in Greece: „That was nothing for an open minded youngster.“

On his trip to Germany he made a four-year stop in Rome in order to study. However, he did not finish his architecture studies there before arriving in Germany.

Compared to his mother’s feeling of strangeness, Efthimios felt welcome. Of course, the way was smoothed years ago when the first wave of Greek migrant workers in Germany built their own social infrastructure in the form of culture clubs, restaurants, Rembetiko concerts and other events. Friends and relatives were also already there and offered him a place to sleep. He did not need to stay in a dormitory paid for by the employer.

„It was like being on holidays. At that time I absolutely wanted to stay there only for some weeks. But ’some weeks‘ turned into 35 years.“

As so often before in the history of mankind, Efthimios fell in love, married and had three children. He started to turn his hobby of cooking into a profession and opened a Greek tavern on the outskirts of Nuremberg.

He smiles through his raddled sparkling eyes, when he jokingly says that the main reason for opening a restaurant was a selfish one.

„It took a very long and hard time to get through all these Schnitzel, Bavarian roast pork, strange sausages and dumplings.“

Food actually presented a problem for daily life. Most people who arrived from Greece could not warm to German food. Yet, there were few or even – depending on the city – no opportunities to purchase the same ingredients as in Greece. Only with time did migrants begin to found import businesses for introducing fruits essential to Greek cuisine, such as aubergines, zucchinis and olives. Based on these products migrants started to cook not only for themselves, but also for the local population in newly created Greek taverns. Restaurants were booming so much so in the 1960s and 1970s that food from Greece became a staple good in German supermarkets.

Apart from that, Greek restaurants represented a miniature cliché version of life in Greece without the daily problems associated with them. They were places of fun, delight and enjoyment. Only Monday was a day off. The owners of the taverns visited each other and spent evenings in discussion, or with tsipouro (the Greek brandy) and Bouzouki music. The Germans took part in this little world, which was often called “Taverna Athina”, by having dinner there. It was a chance to meet people outside the office or the factory in an environment focused on social gathering and communication. The intercultural exchange that took place between the blue-white tablecloths and the neoclassical replica statuettes is not to be underestimated.

Cultural clubbing

Apart from restaurants, cultural clubs provided migrants with another opportunity to socialize. Throughout Germany today, there are about 140 Greek cultural clubs with allegedly around 60,000 members.

Gerd Werner is the director of the German-Greek Culture Club in Regensburg.

He was a young student, when (around 1971) he went to Greece for the first time.

At the time when the cultural club was founded in 1980, there were between 1,000 and 1,500 Greeks living in Regensburg out of a city population of 132,000 people.

At that time, four large companies in particular took on employees coming from Greece. They found jobs in a leather factory, at the Knorr brakes manufacturer and in the textile factories Kaiser and Bleimund. Werner criticizes the working conditions in those factories:

„They caught the Greeks to get their menial work done. The leather and the textile factory were only poisonous for the workers.“

It was very difficult to organize political representation for the migrant workers as long the city was governed by the conservative Christian Social Union throughout the 1980s. They obstructed the plans of activists, who tried to establish representation for migrants in general. Most foreign workers in Regensburg came from Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey. They did not enjoy any real opportunity to articulate their interests and problems in city politics. However, when the Social Democrats took over the mayoralty of the city Regensburg in 1990, it was no longer difficult to establish an institutional mouthpiece for the migrants in the form of the Foreigners’ Advisory Council.

Before the cultural club’s founding in 1980, Greek migrants faced an awkward situation. In the late 1960s and early 1970s it was the ‚Diakonisches Werk‚, a protestant charitable organization (the equivalent to the Catholic Caritas), who looked after the interests of the new inhabitants from Greece. For example, they employed a social worker from their native country. However, what could a single person acting as the contact person for 1,000 people possibly achieve?

Even worse, this social worker was sent during the rule of the Greek military dictatorship. It appears that he was a junta sympathizer, whose main task was to monitor Greek workers. This created a challenging situation for those Greeks in Regensburg who detested the dictatorship; the only person who apparently represented their concerns was a man of the junta. This made many Greek workers afraid to return to Greece. They surmised that the problems they had with the social worker in Regensburg would affect their life back home. Not only the social worker, but also other loyalists to the junta, who came as workers, posed a threat to the junta’s opponents.

Such fears were not groundless as the Greek government, also after the dictatorship’s fall from power, tried to intervene in the life of the migrant workers. Werner recalls about the work of the club that, „the Greek embassy intervened and tried to influence the club’s work by quite a number of letters – and this six years after the dictatorship!“ A paradoxical situation emerged: the club wanted to provide the Greeks with a feeling of being home, a place where they did not feel as strangers in a foreign country – and then the Greek government tried to ruin these plans, Werner says.

At the centre of the club’s work, were cultural activities that were designed to create an atmosphere in which the Greek workers could maintain their way of living, for example by celebrating their national and religious holidays. Beyond that, the club also organized financial aid for individuals in need. Gerd’s voice gets thoughtful when he starts to tell the story:

“Four years ago a social worker called from Thessaloniki. She told me there was a man suffering from a rare hereditary disease. The only way to ease his ailment was a microsurgical treatment in the United States or in Germany. The problem was that he had run out of money and couldn’t speak German. We collected about 5,000 Euro, provided an apartment, paid the flight and arranged the medical treatment. Within three months he could undergo the operation. Unfortunately he died last year.”

In contrast to many other Greek cultural clubs in Germany, the club in Regensburg also has German members and even some from Turkey. One of its major goals is to avoid the emergence of parallel societies, by organizing events where Greeks, Germans and also Turks can come together, relate their experiences and defuse persistent tensions.

Once Gerd and other members of the German-Greek Culture Club in Regensburg even organized a panel discussion about the conflict between Greeks and Turks.

“It was very much an emotional argument between Greeks and Turks. They were forced to deal critically with their own past because they directly faced each other, rather than separated in Greece and Turkey.”

This could be a small step for overcoming deeply traumatic collective memories on both sides. To do it in Regensburg was an original and unusual starting point because here, both groups were in the situation of being strangers in a foreign country. They could not count on a majority that would support their interests, so they had to engage with the opposite side. Afterwards the intercultural work between the German-Greek and the Turkish cultural clubs in the city became more intensive.

A few days later Efthimios sits, with a plastic cup of coffee in his hand, in the front of a Turkish food market near the old slaughterhouse in the harbour of Regensburg. He bought a few things for a friend’s restaurant. Nine years after he turned his back on Germany, he seriously starts considering coming back and creating a new life for himself.

“I became more cautious. How many attempts does a 62-year old still have? Most likely not as many as 35 years ago.”

What next?

What conclusions can we draw from this story? What is the added value of an individual life story? What kind of useful information can be obtained from it? I believe that not only general conclusions matter, but also the life experiences of individuals which are always unique. The representation of one migrant experience can help us to not only understand what migration means to people, but also how they felt about it. This essay, therefore, does not claim to produce new knowledge. Its aim is to create empathy by describing the experiences and emotions of a human being. It is not up to the author to draw final conclusions and wide-ranging interpretations from these. Rather, the individuals behind the aggregate story of labour migration should receive their own voice.